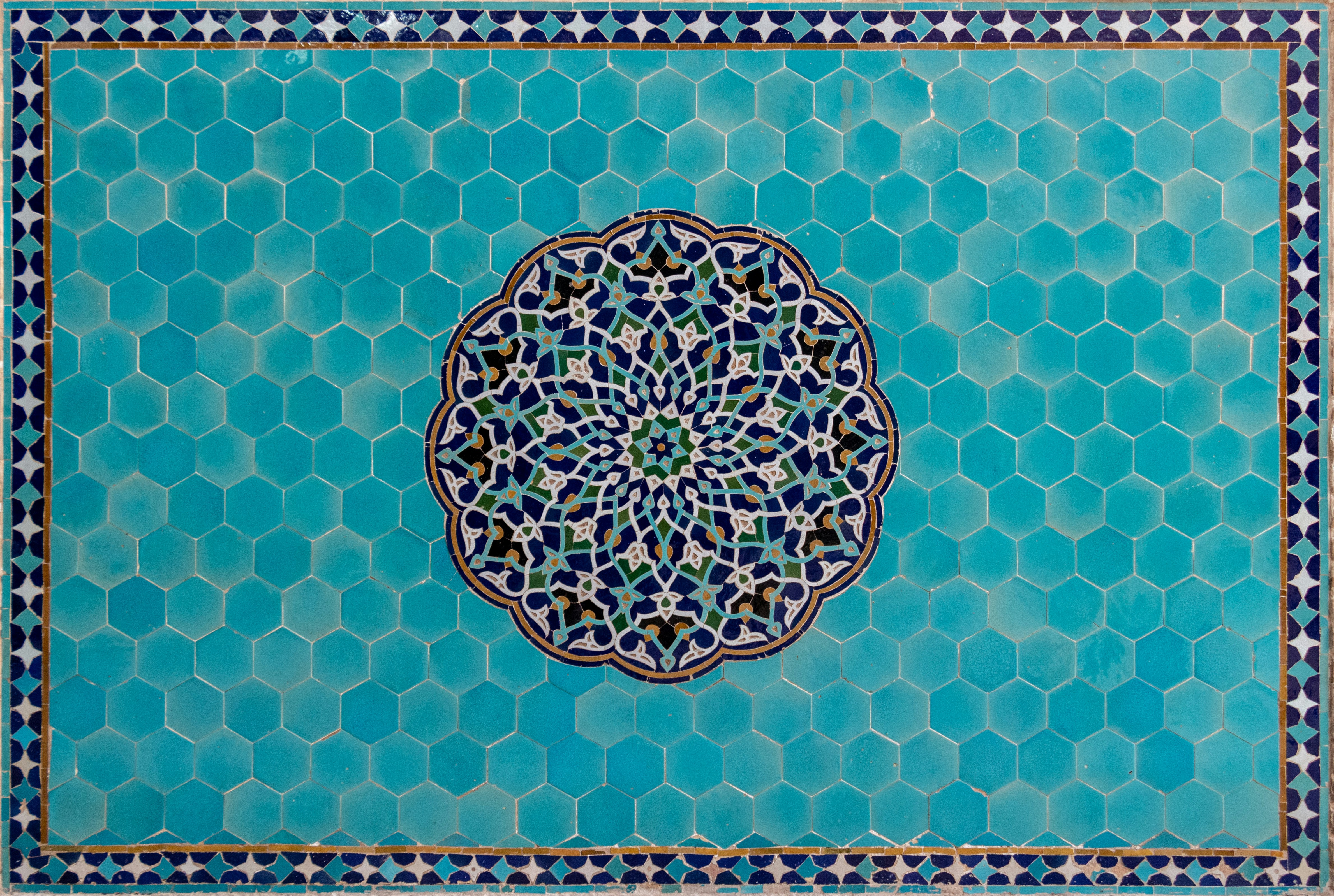

Gems of Iran - The Art of Being Iranian: A Celebration of Persian Aesthetics

February 16, 2026 - The Coat She Could Not Let Go

I don’t want to repeat myself. I don’t want every entry to feel like the same wound reopened. But grief does not move on command. It returns in waves, in images, in moments that refuse to be swallowed.

Today it was a mother.

I saw a brief video clip. Nothing dramatic in its setting. No crowds. No chants. Just a woman collapsed into her own sorrow, clutching a coat that belonged to her son. He was murdered by the regime for wanting freedom. She held that coat as if it were him. Pressed it to her face. Inhaled deeply. And then she broke.

It was the scent that undid her.

The scent of her child still living in fabric while he no longer lived in the world.

The Weight of What Remains

There is something unbearable about the objects left behind. A jacket. A pair of shoes. A phone with unanswered messages. They become relics, charged with memory. They hold warmth that should still be there.

That mother wasn’t holding cloth. She was holding what was left of her son’s presence. She was searching for him in the only way she still could—through scent, through texture, through memory.

Grief is not abstract in Iran. It is physical. It has weight. It has smell. It has a place at the table where someone no longer sits.

The Cost of Freedom

We speak of protests. Of regimes. Of politics. But behind every headline is a mother who must now live in a world without her child. Behind every slogan is a bedroom that will never be entered again.

This is the true cost of repression.

Not just the body lost—but the echo that follows. The birthdays that will pass. The silence in the house. The coat hanging where it always did, but never to be worn again.

No government decree can justify that. No speech about “order” can erase it. No manufactured conspiracy can make that grief reasonable.

Why This Matters

It would be easier to look away. To scroll past. To guard the heart against breaking again. But if we turn away from the mother, we turn away from the truth.

Her grief is evidence.

Her tears are testimony.

Her shaking hands gripping that coat are a record no regime can rewrite.

The regime may try to control narratives. It cannot control a mother’s cry.

Where Hope Still Lives

And yet—even here—hope exists.

Not in denial of her loss. Not in pretending this pain will fade. But in the fact that her son did not die quietly. He did not disappear without meaning. He stood for something larger than fear. And because of that, his life will ripple forward.

Freedom, when it comes to Iran, will not erase her sorrow. But it will give it context. It will mean that his death was not simply crushed by tyranny—it helped dismantle it.

Her tears water something the regime cannot see.

In Closing

I do not want to be repetitive. But how can grief not repeat itself when the violence continues? How can we not return to these images when they are the truest reflection of what is happening?

A mother holding her son’s coat.

Breathing him in.

Refusing to let go.

May we never become numb to that image.

May we carry it with us—not to drown in despair, but to deepen our resolve.

Because as long as mothers are left weeping like this, the demand for freedom in Iran will not fade.

It will only grow stronger.